When his double-jointed party tricks suggested something more serious than a physical quirk and hinted at a syndrome, it marked the beginning of Sydney's journey from diagnosis to open-heart surgery. Sydney has Marfan syndrome and the attendant complications, but he has prevailed and wants everyone to know it will be okay.

by Sydney Heighington, AKA Marfan Squid

Growing up with Marfan Syndrome is a real struggle. As you get older, your toes begin to curl, and your breastbone pushes out, trying to escape your chest. Suddenly, all the double-jointed party tricks you can do seem to be more than just a quirk. They are a sign. As the years pass, you’re told nothing is wrong throughout your many, many hospital visits. You start to feel alone. You know something’s not right. There is one person who believes in your struggle more than any doctor: your mother. She is your guiding light, the reason you finally get the answers you need. She fights for you, year after year, until one day, when you are 14, a doctor not-so-subtly asks if anyone in your family has ever died, suddenly. This is how you find out…

Growing Up: Syd and the Small Kids

From the moment I was diagnosed until the day I had heart surgery, I lived a fairly normal life (although, I think I mostly disassociated from the reality of my condition – it being too much to comprehend…). Yes, I broke most of my bones and, yes, I spent a lot of time in the hospital. Yes, I was blind, brittle, and broken, but I made those things a part of who I was, refusing to let them define me. I embraced my skinny body and height, even naming my band “Syd and the Small Kids.” It got me down, but it never defeated me. Still, there was always that looming presence, stitched to me like a cold and constant reminder that something in my life was waiting for me — a problem for future me. Heart surgery.

Heart Surgery on the Horizon

My dad would always take me to my appointments in London. He often grew frustrated with the lack of understanding around Marfan Syndrome. At that time, I was only being seen from a cardiac perspective, and we were frequently shuffled between different heart doctors. Some of these doctors would ask the same existential questions about the lifespan of my family members. “Has anyone in your family ever suddenly died?” seemed to be the prevailing question, again and again. This, in turn, only deepened the fear of mortality that I was already grappling with.

I probably thought it would never happen, if I’m honest, but it did. I felt it coming one day, sitting in the BARTS Grown-ups Congenital Heart Disease (GUCH) department. It was after a routine appointment — something about my scan was worth looking into, doctors seemed to be more active than usual. I felt it in my bones that it was time. I cried to my wife and my parents when the doctors told me, because the thing I had tried to bury had finally reared its unsightly head.

Anxiously Waiting the Date for Surgery

The next year was not pleasant. It doesn’t matter how many doctors you see and what they say to make you feel better. Your animal brain is wired to conceive the worst. You will die from complications, your aorta will rupture before they have time to operate, an inexperienced nurse will make a mistake during your recovery. You name the irrational fear, I concluded it. My only advice is to talk about it. Don’t ever bottle those feelings up. It’s ok to talk.

There were moments when I forgot, and there were periods that were stable, but I’m not going to lie, the anxiety was awful. This was because no one I knew, or could find, had gone through this procedure for prevention. The Marfan Foundation helped massively with some of it, but there was no one that had gone through this procedure that could physically tell me, “You’re going to be alright.” Mostly people who had been “saved” from aortic rupture, but that just stoked the fears.

Things changed when I met my surgeon, Dr. John Yap. Never had I encountered someone so confident in the face of fear and mortality. With charisma and conviction, he said something along the lines of “...since I’m doing your surgery, I predict a 98% success rate, and the 2% is what’s associated with all surgical complications.” After hearing that, I felt an immense sense of relief. There was something about him; he could certainly ‘talk-the-talk’, and after a close friend of mine, Ben, spent some time researching him, it was clear he could ‘walk-the-walk’, and then some.

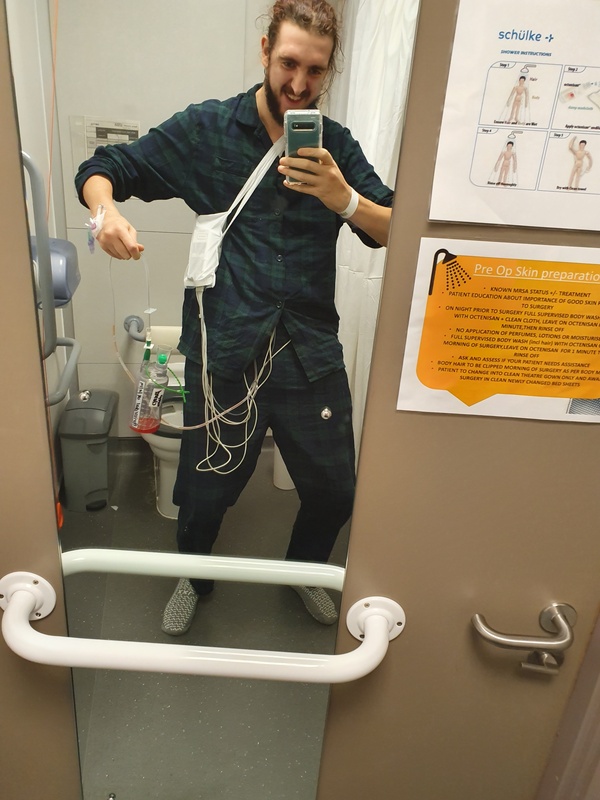

Time trudged by until the day of the surgery — at this moment in time, I’m sure my family and I were in some level of shock as they checked me into the ward and we went for dinner together. Perhaps I had assumed that they were “ok” or “coping” but they were probably all donning a brave face for me. I had lots of medication to keep me calm — the doctors offered the good stuff for nerves. That night, I shaved my legs and went to bed. Unable to really think of what the next day held.

I woke up on the morning of 29th October 2019, took a sedative, was placed in a wheelchair, and sat in a side room with my mum and my wife. I don’t remember much — I was heavily sedated — but I do recall my wife putting Kitchen Nightmares on the small TV in the room. I chuckled at the attempt to preserve some sense of normalcy.

About half an hour later, I was wheeled away. As the nurse reversed me into the lift, I said goodbye and “I love you” to my family, watching them crumble under the weight of holding back their emotions as the doors slid shut.

Then I was there, lying back, looking up at the ceiling. I thought to myself, It doesn’t matter anymore — I’m in Dr. Yap’s hands now. I had faith as I counted back from 100 and reached 94.

I’m not the same person that walked into that hospital in October 2019. I had a stroke during my surgery, potentially due to a hole in my heart that they had not previously identified. My aortic valve was also worn down and likely irreparable, so the operation was more complex and lasted longer. They replaced my aorta, put in a mechanical valve, and apart from the stroke, the operation was a complete success. I’d expect no less from the legendary John Yap. Still… it changed me.

Being in the HDU was crazy. I was pumped full of Fentanyl and monitored every couple of minutes. Once they felt I was stable, they moved me to a ward.

I wasn’t stable.

My heart rate was consistently reaching into the two-hundreds, and the ‘line’ in my neck supplying me with pain medication was left in for too long (mostly due to extended suffering/pain that they hadn’t anticipated). Due to this, and a huge build-up of fluid in my chest cavity, I went into septic shock within moments of them removing my neck line.

I don’t recall much of the next half a day. My wife remembers Dr. Yap stepping out of the elevator after the emergency call and reassuring her with unwavering certainty that he would fix me no matter what the problem was. It still astonishes me that a human being can speak such words and truly believe them.

I spent the next two days in an ICU bed, slowly feeling myself slip away. I felt like I was dying, but I knew I was safe in the ICU. After days of panic and confusion, my second saviour arrived: Dr. Bejal Pandya. She had been my Marfan specialist and cardiologist since I was about 22. When she entered the room — hurried back from holiday and still in her “outside clothes” — everything changed. The atmosphere shifted from finality to certainty. I knew then that I would be okay.

Dr. Pandya arranged my second surgery, and within hours I was back under the knife — this time to drain the septic fluid from my lungs. When I awoke, I felt alive again. Not recovered, not yet — but the feeling of illness that had settled in my bones had dissipated. I felt like myself again.

It was then at least another month of bed rest and monitoring, as my temperature and inflammatory markers refused to settle. The doctors suspected I’d contracted a post-surgical infection, so — to be safe — they put me on a course of Gentamicin and Vancomycin: the strongest antibiotics they had.

I had also suffered from pneumothorax — my lungs had collapsed due to the fluid and surgery, so I had to use a nebulizer to slowly repair my breathing.

Eventually, I was released home with my wife, and I cried the moment I stepped through the front door for the first time in almost a month. Sadly, this was not the end of my trauma.

A week or so passed, and I grew increasingly unwell. My urine was discoloured, my fever spiked, and I began to vomit blood. My wife rushed me to A&E, where I was admitted once again. It later became clear that the antibiotics had injured my kidney, though this wouldn’t be fully understood until later.

I spent another month in hospital — first at Lewisham, where I continued to vomit blood and required transfusions, before being blue-lighted in an ambulance to Guy’s and St Thomas’. That’s where my third saviour, Dr. Niel Ashman, came to my rescue.

After some deliberation over whether I had developed an infection on my heart valve, the plan was to carry out an endoscopy to take a closer look before deciding on the next steps. If signs of infection were found, I would need further heart surgery. If not, Dr. Ashman’s prediction was that I had suffered an acute kidney injury, and would need treatment to recover fully. He was right. I had every faith he was.

Finally, after being taken off antibiotics and given steroids, I began to feel better — and by Christmas, I was finally sent home to recover fully and begin the long journey of processing everything that had just happened to me.

Months passed. With rest and gentle exercise, I began to heal physically. I did suffer from post-traumatic stress, and I’m still on medication to help manage that. But after everything — after all of it — I am stronger and healthier than I have ever been.

Life after surgery isn’t without its challenges — don’t get me wrong. I live with the ongoing stress of anticoagulation therapy, and I still have Marfan Syndrome and its many associated complications. I take a lot of medication, but all of it helps me live a better life. It’s a life supported by medicine, yes — but one I’m deeply grateful for. I see it as a blessing that we live in an age where such treatment is even possible.

In 2022, I went on to achieve great success — both professionally and personally. I released music about my experience, spoke in front of thousands at the National Education Union (NEU) Conference, and was promoted to Assistant Headteacher. All of this came from a renewed desire to live — not just survive, but to live stronger and better than before. I also joined my wife on a journey of sobriety — of which we are now over six years sober.

I’ve mentioned my three ‘saviours’, as the people I practically owe my life to, but there is one other person who held me up through it all. My wife. She went sober with me to support me pre-surgery, she picked me up when I was down, she held a brave face and never ever left my side. She’s my real true saviour in all of this. I owe her just as much.

It's Going to Be Okay!

Now that you’ve heard my story, I want to reassure you: it’s not meant to cause alarm if you’re waiting for your own preventative surgery. Instead, it’s intended to show that even in the worst-case scenario, it’s possible to come through the other side — healthier, stronger, and more resilient than before.

Dr. Pandya told me that what happened to me became a major learning opportunity for surgeons and post-operative care teams working with Marfan patients undergoing this procedure. She made it clear that others would not have to endure the same traumas I did. Surgical techniques have continued to advance — procedures like PEARS now offer even safer, more effective options for patients like us. She made me feel like my suffering wasn’t for nothing.

I also finally invite you to visit my Instagram page, @Marfansquid — it’s the platform I use to connect with fellow Marfs, share my journey, raise awareness, and offer advice and encouragement.

Take it from me: you’re going to be okay.